Technology

New science, technology, and predictions create urgency for California earthquake coverage

Earthquakes are a reoccurring danger in California, and fears of “the big one” hitting are not completely unfounded, according to seismologists. The likelihood of a magnitude 6.7 or larger earthquake occurring somewhere in California in the next 30 years is a near certainty, they say. This staunch warning comes on the heels of new technology that’s improving scientists’ understanding of earthquakes. Insurance companies, state governments, and other stakeholders are tapping into this new technology to find ways to predict, assess, and mitigate earthquake risk through emergency preparedness, infrastructure improvement, and more readily available and affordable insurance. For California residents, it can’t come soon enough.

How earthquake science can upend earlier risk predictions

For decades, California has relied upon the Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast (UCERF) model, produced by the U.S. Geological Survey, for forecasting the magnitude, location, and likelihood of earthquakes throughout the state. Updated as the science progresses, the models become more accurate, detailed, and sophisticated with each iteration. For example, the 1988 model considered 16 different faults, a number that increased to 200 in 2007 and to more than 350 in 2014.

The latest model—UCERF3 in 2014—diverted from the 2007 model in that it found that faults are not isolated as previously thought, but interconnected in a broad network where nearby faults can rupture simultaneously. This new awareness led to the prediction that California would experience less frequent moderate quakes (magnitude 6.5 - 7.5), but the likelihood of a larger event is greater than earlier predictions.

The 2007 forecasts placed the expected frequency of a 6.7 quake somewhere in the state at one every 4.8 years. UCERF3 predicted the frequency of a 6.7 quake at one every 6.3 years. This is good news, but what about the bad? The UCERF3 model now forecasts the likelihood of a magnitude 8 or higher from a 4.7 percent chance in the next 30 years to a 7 percent chance.

New modeling technology provides the missing piece for risk estimating

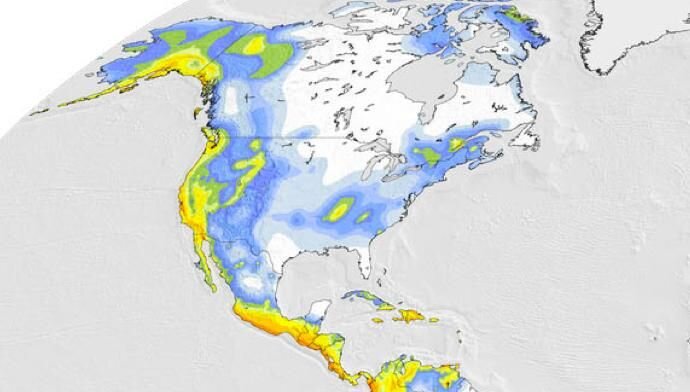

To fully understand and estimate California earthquake risk, stakeholders must be able to quantify the uncertainty through robust modeling. UCERF3 is one of two types of earthquake models—an earthquake rupture forecast—that predicts where and when the earth might slip along a fault. The other—ground motion prediction models—estimate the subsequent shaking resulting from a fault rupture. This second type is critical in formulating policies around risk mitigation, emergency preparedness, and the design of buildings and infrastructure. Insurance companies, city planners and other stakeholders use commercial risk modeling software to help estimate the resulting effects of ground shaking, including damage to structures, economic losses, casualties, and business disruption.

A problem with these proprietary models is that they’re protected as intellectual property, so users can’t evaluate all the underlying assumptions and methods used to create them. This lack of transparency makes them difficult to use in earthquake risk management. The Global Earthquake Model Foundation (GEM) attempted to solve this problem by creating open source earthquake hazard and risk assessment modeling software called “OpenQuake.” This software lets users select or substitute every model component, which helps them better interpret the risk assessment results, put more trust in the results and, ultimately, make better risk management decisions.

The insurance implications of following the science

New technology like OpenQuake is helping insurance companies to better understand and quantify earthquake risk, which will be necessary in order to stabilize premiums and attract more homeowners to purchase earthquake coverage—something they haven’t seen included in their homeowners’ policies for many years. Californians have been on a wild ride that’s left many dissatisfied with earthquake coverage, and only about ten percent of residents purchasing policies. Those with coverage are learning that their premiums are not so much tied to recent history—such as the twin quakes that hit Southern California in July of 2019—but to the latest scientific evidence posed by UCERF3. Following those quakes, a quarter of the one million Californians who purchased earthquake insurance saw premiums double or even triple in some cases. The increases were concentrated primarily in the Los Angeles area while other parts of the state, such as San Francisco, saw decreases. About ten percent of homeowners in California obtain residential earthquake insurance from the California Earthquake Authority (CEA). CEA was created following the 1994 Northridge quake that killed 57 people and cost $20 billion in damages. After Northridge, most insurance companies stopped including earthquake coverage in homeowner’s insurance policies and some even threatened to leave the state. CEA—a privately funded but publicly managed organization—underwrites most of the residential earthquake coverage in the state.

CEA spends nearly half of the premiums it collects per year on reinsurance against the possibility of a magnitude 8 earthquake hitting a heavily populated area and forcing it into bankruptcy. Some critics say CEA should be lowering premiums as an incentive for more residents to purchase earthquake coverage. CEA argues that, unlike flood insurance, they don’t have the backing of the federal government if a devastating quake occurs. Like wildfire insurance coverage, the state may be in a position where it needs to encourage more private insurance companies to provide earthquake insurance to the residents of California. Better technology and cooperation between scientists, government offices, and insurers certainly helps, but winning the confidence of homeowners needs to start with transparency and education on the science behind the risk.

©2026 Applied Underwriters, Inc. Rated 'A-' (Excellent) by AM Best. Insurance plans protected U.S. Patent No. 7,908,157.

We use cookies to track some on site behavior. By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our cookie policy.